Welcome back to Crescendo Insights, where we provide a bite-sized piece of monetization strategy each week.

If you’re not a subscriber yet, hit the button below to keep getting these emails delivered to your inbox.

The BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front)

A Quant Study is the best way to assess price metric because it directly correlates willingness-to-pay with different price metrics.

There are easy and hard ways to understand price metric in quant studies. We show you 5 ways. Start easy and work your way up to “ludicrous mode”

Your price metric should be based on solid research, not what is trendy or what your competitors are doing. After all, they might be wrong!

Assessing Your Price Metric with Quantitative Market Research

Welcome to our final installment on price metrics. Next week we’ll take brief interlude before tackling a different piece of the monetization puzzle. So far, we’ve covered the theory behind price metrics, data analysis to inform your decisions, and customer interview techniques. Today we’re examining one of my favorite topics - the quant study.

Let’s dive in.

Ok, but what the heck is a quant study?

Great question dear reader. That’s maybe a topic for another post, but a quant study is another term for a very fancy survey. How fancy you ask?1 It can range from the simplest branching logic all the way to stochastic modeling, also known as a conjoint. But almost all quant studies have one thing in common, at some point in the survey, they determine your willingness-to-pay!

How do you solve a problem like price metric?2

Remember the 4 elements that make a good price metric? Good price metrics need to be feasible, communicable, segmentable, and valuable.

Quant studies are truly fantastic at understanding the most important element: valuable. That’s because we can directly see whether customers would pay more for your product, if you charged on a different metric.

We’re going to take you through 5 levels ranging from Easy to Expert on how to assess metric through surveys. Fair warning, there will be math.

Level 1 - Easy. Just ask your customers.

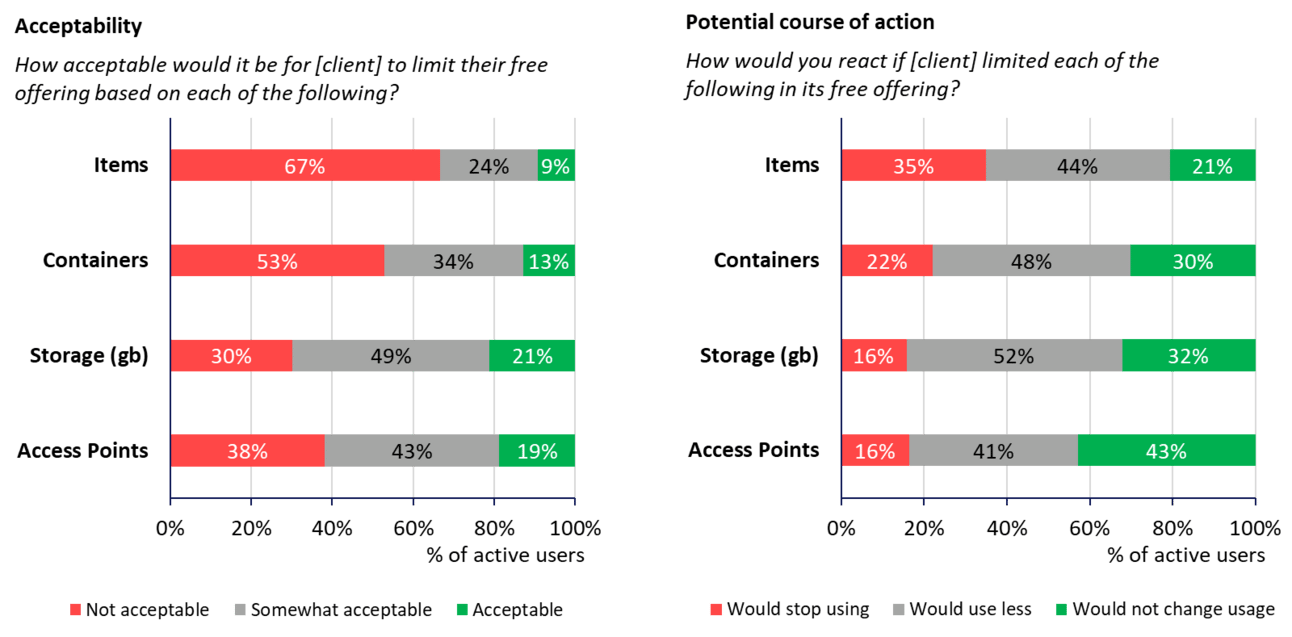

This may seem simple, but it works if you have a big enough sample size. You can often ask customers directly how they would react if you changed your price metric. Warning: customers often over inflate their churn assumptions here, so you’re looking for relative churn risk, not absolute churn risk.

In the graphs above, access points looks like a safe bet, but storage is a close second. FWIW, I care far more about the left graph (perceived acceptability) than the right graph (churn response). The left graph speaks to fairness (aka Communicability), while the right one is a messy proxy for willingness-to-pay. In this project for example, we found that customers had the highest willingness-to-pay for Items, despite them generally thinking that charging for items would be unfair.

Level 2 - Medium. Take an average.3

Once you’ve quantified willingness-to-pay via any number of the methods we will spell out in future posts (reminder to smash that subscribe button), you can do all sorts of amazing analyses on price metric.

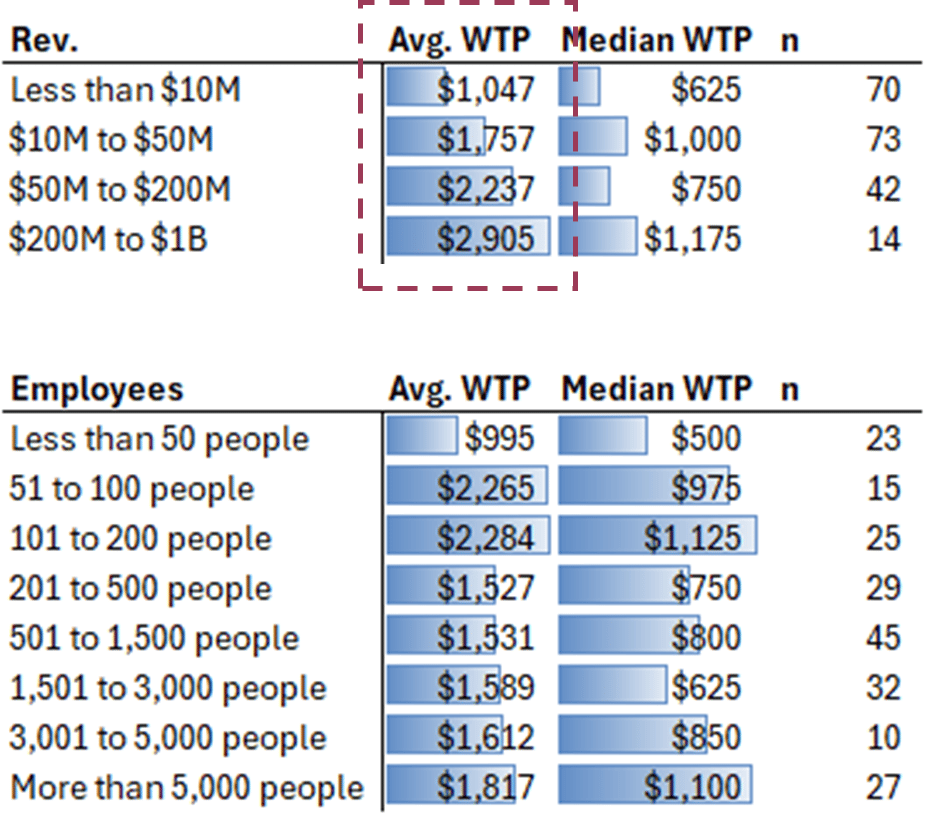

This example comes from the retail and supply chain software industry. The core question we had was “should we do usage-based pricing, or a subscription based on the size of the customer, i.e. revenue or employee count?” I know I came down hard on usage-based pricing a few posts ago, but the reality is that it greatly depends on your company’s market.

In the example below, we first measured each customer’s willingness-to-pay, then segmented those same customers according to revenue and employee count. The three main takeaways are:

Neither revenue nor employee count is particularly predictive of willingness-to-pay. BUT if you had to pick one…

Revenue of the company is a better predictor of WTP than employee count (see red square)

This means that something else is driving willingness-to-pay. Turns out, it was usage.

So what should the company do? Abandon the idea of creating a subscription and charge for usage instead.

Level 3 - Medium-ish. Make a plot, ask Excel to do math.

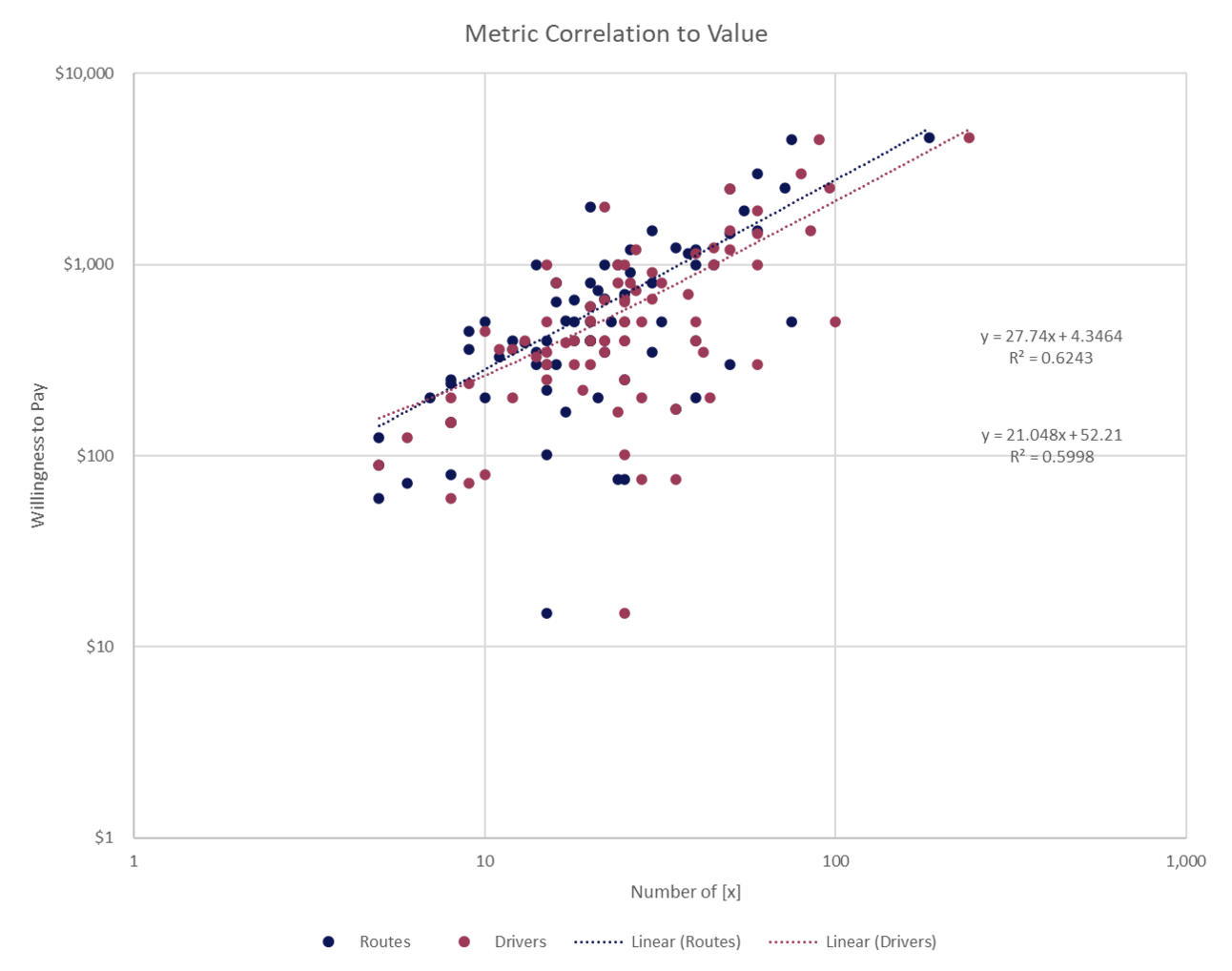

Averages are nice, but sometimes you need to see each customer individually. The following method works best when you’re comparing two simple metrics. If you have some sort of multi-metric pricing model, you’re going to have to do something more advanced. On the plus side, this is quite simple, and because it’s a visual exercise, you can really see which of two metrics predict willingness-to-pay better.

This example comes from the logistics software industry. We have a piece of application software that manages drivers and deliveries. At the time of the engagement, the company priced “per driver,” but they had seen competitors begin to price “per route” and were wondering if they should switch. The problem with switching is that it’s costly; you often need to rearchitect your billing tech stack and re-quote every customer, which inevitably causes churn. Like open heart surgery4, you only want to switch price metrics if you absolutely have to.

The takeaway from the graph above is not exciting. When you compare the predictive value of drivers and routes, they predict willingness-to-pay equally well (R-squared of .59 compared to .62 respectively). Maaaaaybe routes is a little better, but is it worth doing a metric change? Probably not.

Level 4 - Hard mode. Run a regression.

This is hands down the best way to pit multiple (like 10) metrics against one another. If you tried to do that with overlapping scatter plots, it would look like Jackson Pollock’s worst painting.5 A better way is to do a simple regression, figuring out which metric (or customer characteristic) best predicts willingness-to-pay and with what level of accuracy.

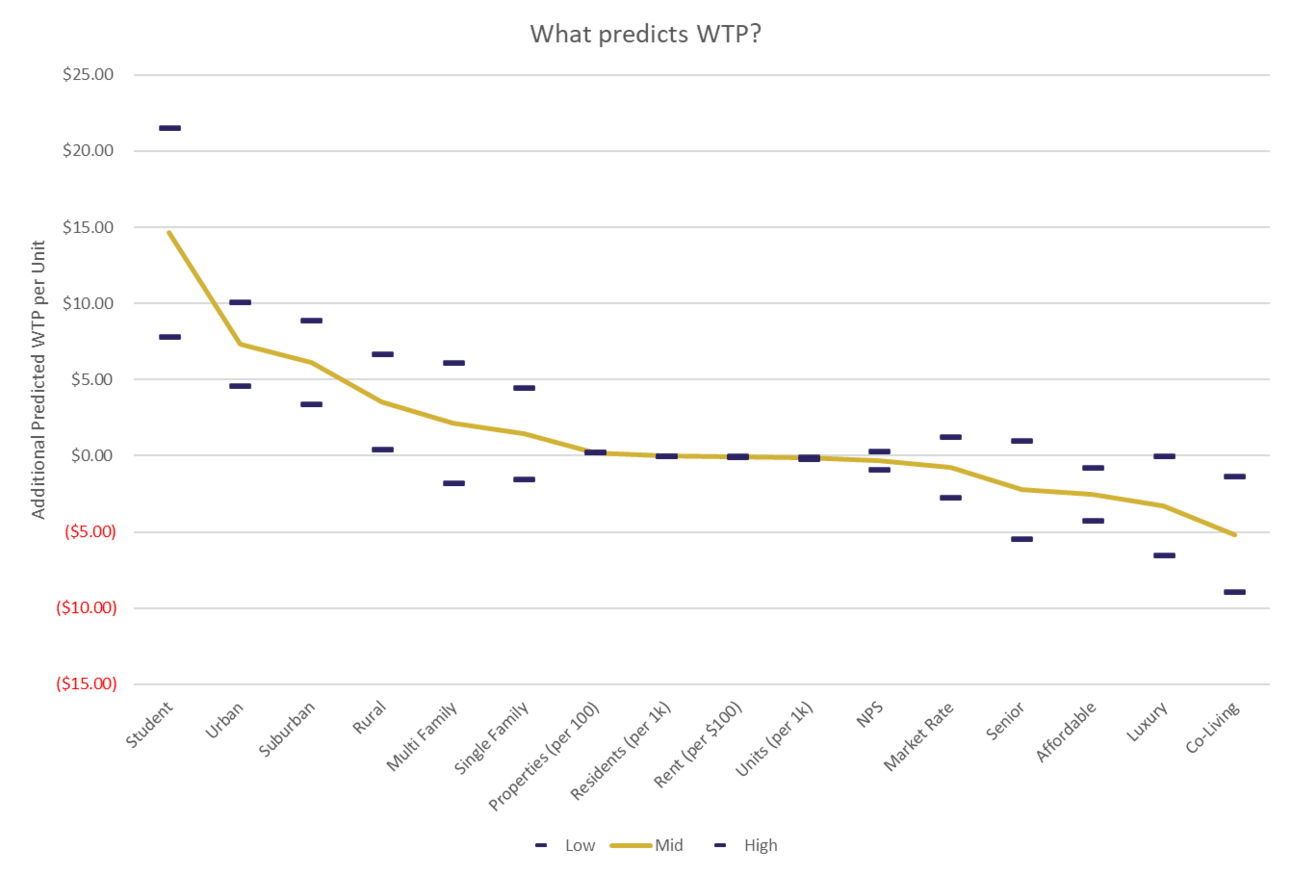

Here is an example from the property technology space. This is a company that facilitates transactions between landlords and renters. Assuming we are charging the property owners, you could charge for the number of residents, the number of units, a percentage of the rent, or a flat fee per building.

The implications here are numerous. If we’re charging for residents, then properties with small units will pay more (per sq. ft.). If we charge a percentage of rent, then luxury properties with high rents will pay the most (on a relative basis). If we charge per property, then a real estate company with lots of duplexes will pay more than a high rise. It’s a price metric smorgasbord!

Let’s do some math. Below is a regression output looking at how well willingness-to-pay is predicted by different property characteristics: size, residents, total rent, and property type. What do we notice?

Let’s look at the middle and compare per property, per resident, per $ of rent (%), and per unit. Properties and residents are better predictors of WTP than rent and units. That means we would be better off charging a flat rate per property, or a rate based on the number of people living in the property, rather than taking a cut of the rent.

So what types of properties would pay more under this price architecture? Ones with lots of people living under one roof or lots of “roofs” (aka multi-family). What type will pay less? Luxury high rises with few people per roof and high rents.

Now look to the edges. Notice how student housing, multi-family, and single family are all high WTP while Luxury is low? That confirms our hypothesis that resident or property based pricing captures value better than a % of rent.

Level 5 - Ludicrous mode. Model it.

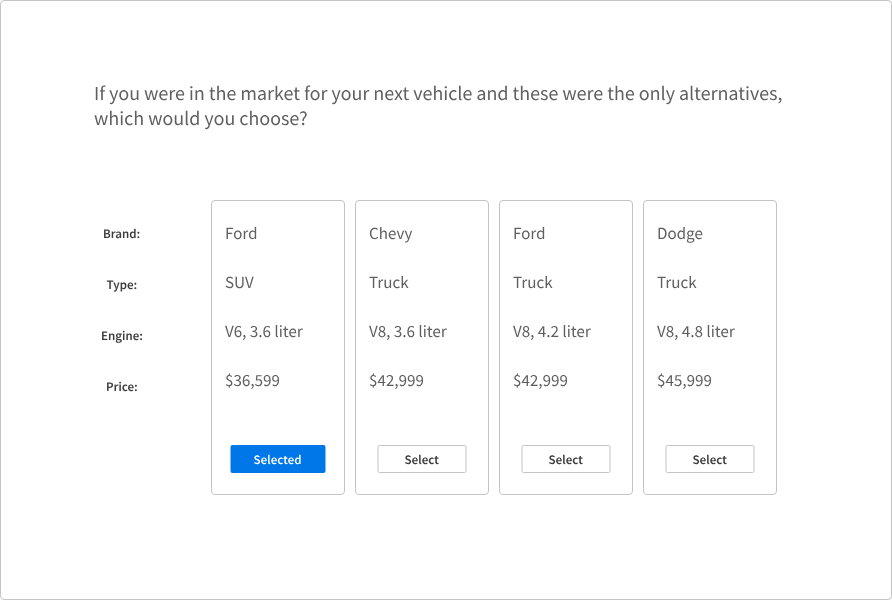

The absolute gold standard for price metric discovery would be to run survey respondents through a conjoint study. There is WAY too much to cover in this post about what that entails, but here’s an example, taken from the OG conjoint software, Sawtooth. You show respondents a screen like this and ask them to pick their favorite option:

Then you mix up the cards, and rearrange the prices, and do it again. Usually 8 times. Once you do that, you not only have each respondent’s willingness-to-pay, but you have their willingness-to-pay for each component of the product. With a little bit of math, you can figure out the optimal metric AND optimal price for that metric AND exactly what it will do to your revenue (including churn) if you adopt that metric. It’s quite powerful.

It’s also quite advanced. Definitely try the other methods first. They are easier to explain, cost $0 to set up, and don’t require a PhD to interpret.

The Takeaway on Price Metric

I was once asked by a well-meaning superior to come up with a list of all the price metrics that a software company could use. I hope you understand by now how impossible and fruitless that would be. The price metrics for our prop tech company (units and residents) in no way translate to our logistics company (drivers and routes), yet those are precisely the key discussions you need to be having as you price your product. The question is almost never “should we do usage-based pricing?” It’s usually “which usage-based metric should we use?”

I also want to emphasize that there is no “right” price metric, only what is right for your market. Spotify should not do usage-based pricing, whereas our supply chain company in example 2 should.

There were also some counterintuitive findings around pricing to revenue. In both example 2 and example 4, we found revenue poorly predicting willingness-to-pay. Remember that wallet size is only one half of what makes up willingness-to-pay - the other half is utility, or how useful is the product. Don’t assume bigger wallets = bigger contracts.

Lastly, you should make sure you don’t just follow your industry or your competition. I hate competitive based pricing and example 3 shows why. Sometimes the competition is doing something that makes no difference to an outcome, and chasing competitors has its costs.

Get in touch

Crescendo works with medium-sized software companies to improve their pricing, packaging, and promotion strategies. If you’d like to book a quick consult, reach out at [email protected] or schedule time via the button below.

1 Top hat and tails fancy

2 Sung to The Sound of Music

3 Or a median, if you’re feeling saucy

4 Which I assume is dangerous. What do I know, I play around with spreadsheets all day.

5 Feel free to debate that in the comments.