Welcome back to Crescendo Insights, where we provide a bite-sized piece of monetization strategy each week.

If you’re not a subscriber yet, hit the button below to keep getting these emails delivered to your inbox.

The BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front)

Time based pricing (e.g. monthly vs. annual discounts) is best understood by analyzing churn data.

There is a simple formula you can use to optimize your time based discounts…or you can break out an Excel-based optimization model.

When in doubt, choose 40%

Pricing Over Time

This week is another reader request, this time from Nicole Zhang over @ Hex. It’s a question we get fairly frequently - how should you think about monthly vs. annual pricing (or multi-year pricing).

This question almost always comes down to “how much discount do you offer to encourage longer contracts?” If your monthly plan is $10 and your annual plan is $100, you’re giving a 17% discount ($10 × 12 months = $120 vs. $100 annual).

So why give a discount at all? Because customers tend to churn less when they are on longer contracts.

At a minimum, you guarantee revenue for the term of the contract. But beyond that, customers also churn less because there are fewer “transactional events”. It sounds simple but each time customers are forced to press “buy” (or call their sales rep), there is a chance for downsell or churn.

Let’s dive in.

Using Data to Optimize Discounts

Timing-based discounts are a fantastic thing to optimize using data analysis because you are examining relative willingness-to-pay rather than absolute willingness-to-pay. For this recipe, you’ll need 4 numbers, 2 of which are easy to find:

Average Monthly Price per Customer (easy)

Average Annual Price per Customer (easy)

Average Monthly Retention (medium)

Average Annual Retention (hard)

In case you’re wondering, average annual retention is hard to get because it literally takes a year to measure. If you’ve had both types of plans for at least 1 year, you’re in the clear, otherwise you may have to make some assumptions.

By the way, the analysis is the same if you’re comparing weekly prices or multi-year prices; you just need the appropriate prices and retention rates.

Gut Check: How much discount should we give away?

Let’s do an example. Imagine we have a SaaS product that we sell for $10 monthly and $100 annually - that’s our standard 17% monthly to annual discount. For what it’s worth, this is the most common monthly to annual discount out there.

Now let’s further imagine that our annual retention is 70% and our monthly retention is closer to 95%. Given only those numbers, how large should our monthly - annual discount be?

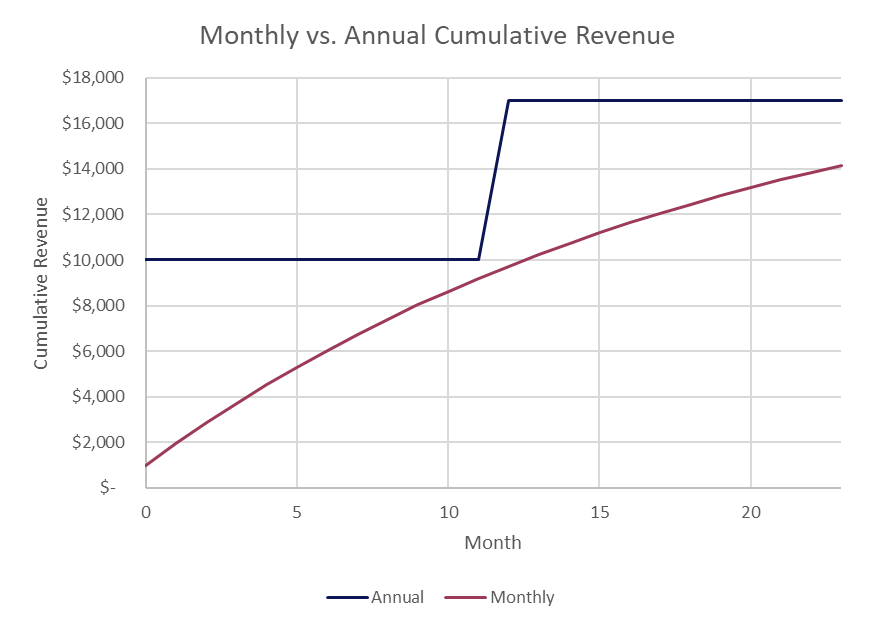

Let’s take a look at the first 24 months of 100 monthly customers and 100 annual customers. The graph below shows each cohort’s retention.

By simply multiplying P * Q, you can calculate each customer cohort’s 2-year-cumulative-revenue1.

It should be pretty clear to everyone that Annual customers are better. That’s not interesting, we already knew that2.

So what’s the optimal discount? Well, a good pricer should be indifferent to selling customers a monthly or an annual plan3. We should be willing to incentivize customers enough, such that both plans have equivalent cumulative revenue, either by raising the monthly price or by lowering the annual price?

How much? Well we ran these numbers though an optimization program and the point at which monthly 2-year revenue and annual 2-year revenue intersect is at a 31% discount, or $83.29 for an annual plan.

Unpacking LTV

Of course what if your customer lifetimes are longer than 2 years? What if your retention numbers are so high that your cost of capital starts to outweigh your churn? That’s when we need to start bringing customer lifetime value (LTV) into consideration.

Because we work with both VC and PE backed companies with wildly different software retention rates, we always adjust our LTV calculations by a weighted average cost of capital (WACC). For VC backed companies with high growth and low retention, the cost of capital barely affects it, while in PE, it has a massive impact. I’ll save my LTV diatribe for another post, suffice it to say that our formula for LTV is below:

Fight me in the comments about my calculation

For most of our clients, we use a WACC of 10%, but it doesn’t honestly matter much for our core discussion of monthly to annual discounts.

One formula to rule them all

So how can we arrive at an optimal monthly - annual discount without having to break out an optimization model? Answer: a lot of math.

If you’d like to email me for the full derivation of the formula below, feel free, otherwise just copy, paste, and trust me.

Drum roll please…

Formula for optimal monthly - annual discount

If you’re dealing with a different time horizon (like annual to quarterly or 3-year to annual), you need to adjust that “12” accordingly. Let’s run our scenario through this formula:

If our annual churn is 30%, our monthly churn is 5%, and our cost of capital is 10%, then our optimal discount is 43%.

43%?!?!? Isn’t that super high? Not really. Let’s graph it out. Here is the 6-year cumulative revenue graph for a $10 monthly plan and a $68.57 annual plan, keeping those same churn assumptions. Notice how the two lines start to converge?

Special Situations and a Rule of Thumb

In each of the examples above, we’ve assumed that by converting monthly customers to annual customers, you retain the same churn rate. That’s obviously a big assumption that doesn’t always hold. You should constantly monitoring your customers’ LTV in both plans to make sure that you aren’t making an “all else equal mistake'“.

Another issue is your own personal time horizon. As you saw in the examples above, if you take a longer term time horizon, your annual price will be higher than if you take an infinite time horizon. This is a classic revenue now vs. revenue later issue. Do you give customers a sub-optimal discount to juice revenue now at the expense of long term LTV?

Lastly, we’ve been talking about perpetual monthly to annual discounts, but it might be an optimal strategy to give 1 time conversion discounts, e.g. a promo code sent via email. This is a great thing to a/b test4 , since it’s fairly easy to randomize email cohorts.

Lastly, if you have no data, and want to play around with this, I have had multiple clients find success with 40% monthly to annual discounts. Why 40%? I have no idea, but I’ve now seen it multiple times in multiple industries. Maybe it’s just south of 50%? I have no clue. Anyway, when in doubt, try 40% off.

But what if I don’t have any churn data? How do I set my discount then?

In our next post, we’ll talk about the theory behind monthly to annual discounts and how you can make an educated guess about where you should be.

Tune in next week!

Get in touch

Crescendo works with medium-sized software companies to improve their pricing, packaging, and promotion strategies. If you’d like to book a quick consult, reach out at [email protected] or schedule time via the button below.

1 Also known as 2 year LTV

2 Maybe you didn’t because you thought 95% monthly retention was good :)

3 Much like how the bank doesn’t care if you buy a fixed or variable rate mortgage

4 A sentence I never say ever